A Wendigo in Westtown Woods?

Students on the hunt for mythical creature

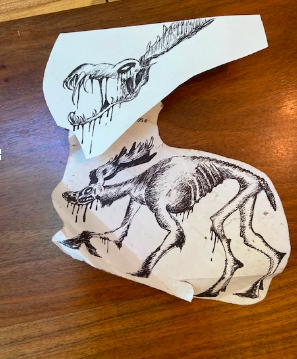

A Westtown student dreamed of the Wendigo, woke up and created this illustration.

April 24, 2023

“We go in the woods with long metal poles and we look for wildlife with no flashlights,” said John Martini ’23.

Back to the times when Lenape settled on this land, they left their cultural trace in the forms of customs, traditions, and beliefs. Every tribe had its own, unique and inimitable characteristics. But there was one thing that united all of them – fear of a Wendigo.

Fear that shackles your body, leaving only quiet trembling to show that you’re still breathing. Fear that makes your muscles numb and leaves only cold drops of sweat running down your neck. Fear that paralyzes your mind and tears your vocal cords from desperate screaming. It’s the terror of being eaten alive.

Westtown School finds itself on pristine, verdant, and remarkable land. Its soil is soaked with history and heritage that people left throughout hundreds of years. While here, students connect with the past and present. The experience of being here may be considered a blessing. But could this grace also contain its curse?

As the website Legends of America tells it, in Indigenous myths, the Wendigo is illustrated as a supernatural cannibal with extremely sharpened eyesight, hearing, and physical senses. It’s an evil spirit, which represents gluttony and greed. Wendigo are depicted as ginormous humanoids, twice a human’s size, with pulled skin flaps and unhealed wounds all over its body. Its red eyes are pushed deep into the eye sockets, and its mouth-shaped hole is covered in dried blood. The Algoquian legend describes it as, “a giant with a heart of ice; sometimes, it is thought to be entirely made of ice. Its body is skeletal and deformed, with missing lips and toes.” The legend also mentions that, with Wendigo’s appearance, the air instantly cools down and ice-cold wind penetrates the skin. At this point, it might be too late to run.

According to the Canadian Encyclopedia, a Wendigo always looks out for human flesh. It never sleeps, it never rests. Whenever a Wendigo devours a person, it grows in proportion to the meal it has just eaten, therefore, it is never full. And it’s impossible to escape. The Wendigo’s curse enters not only the human body but also the mind. Wendigo can possess people, while they are asleep by calling their names, so they wake up with insatiable hunger, and break tribal taboos by filling their stomachs with human flesh.

Many Indigenous peoples have traditions of being animists, so they perceive life in every single thing. The biggest crime possible would be to take life away. It’s interesting that thousands of years later, the term “windigo” penetrated the medical vocabulary. Missionary J. E. Saindon was the first person to use the term to describe patients with depression, anxiety, and intrusive cannibalistic thoughts. Later on, this condition would be called “windigo psychosis,” It would be considered a dangerous mental disorder containing two stages: withdrawal into melancholia, insomnia, hallucinations, and ferocious violence, which may follow immediately after the first stage. However, in his doctoral dissertation about Windigo Psychosis (1960), Dr. Morton Teicher described over 40 different cases of Wendigo possession, and only two of them had symptoms before turning to cannibalism. This puts us in a controversial position, as the disorder symptoms are ambiguous and delusional.

Despite the horrific danger of any kind of involvement with the Wendigo, Westtown students, Santi Benbow ’23, John Martini ’23, and Tommy Tang ’23, decided to hunt it down.

Starting this year, Santi Benbow began chasing the Wendigo after a series of weird coincidences, which made him assume that he’d met the creature.

Back when Benbow was in ninth grade, he used to live behind Westtown Lake. After the study hall, when no sunshine would guide him in the darkness of the night, he would walk through the woods by himself to get home. One night something happened.

“I get down the hill, and when I look up, I see deer – which is normal,” Benbow said.

“The moon was out, and so it lit them up on the horizon. One of them was bigger and taller. Then I walk by and I smell something awful. The deer kind of retreated into the woods by this point. I take out my flashlight and see a mangled deer carcass. It looked like it was fresh. And then I ran. And the next morning, I went to show [the carcass] to others, but it was gone. There was nothing there. Which was kinda weird. But I didn’t pay a lot of attention to it until last year when Teacher Reece told me that there is a Wendigo in our woods.”

This information confused Benbow as he never told Teacher Mauricio Torres ’08, his story about the deer, so how would he know, right? But then Torres shared his story, and it suddenly connected all the dots.

Back during his student years at Westtown, Torres went out with a handful of other folks when he spotted a mutilated deer carcass, pure carnage.

“It would have looked prettier if it had been hit by a truck,” said Torres. “I’ve never seen a body of a mammal in those shapes and that condition, ever. And Teacher Michael [Williams ’09], who was also there, was immediately concerned, upset, and proceeded to bury it, with the utmost emergency.”

“ That was the first time I encountered the notion that there was something in our woods other than us,” Torres said.

Unlike our current hunting trio, Torres avoided meeting the cannibal.

“To seek the Wendigo is to invite the Wendigo. To invite the Wendigo is to be aware of its presence,” said Torres. Once, Torres recounted, he went on a walk with his dog, Duke, who is extremely responsive to his name. With earbuds in his ears, Torres was intently listening to his music. Through the music, Torres heard something calling his dog’s name again and again. He took his earbuds out, but it was like the wind itself produced the sound.

“It’s like the woods were calling my dog,” Torres said.

After that, Torres put his headphones in and left the woods without acknowledging the creature’s presence.

So, is the Wendigo real? Can those legends and myths be trustworthy? Is the evidence of encounters with the Wendigo enough to prove a presence of a mythical cannibal in the Westtown Woods? Judgment and beliefs are an individual system, everyone must draw their own conclusions. But there’s one thing we all should remember: each tale has a true origin to it, and, perhaps, not knowing the truth is our saving.

Ron • May 9, 2023 at 12:12 pm

This was a wonderful, fascinating read! Thank you!

Ron Maurer

Security